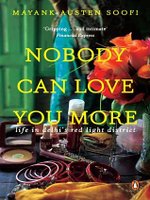

Nobody Can Love You More

Mayank Austen Soofi

|

|

If there is one sentence in Mayank Austen Soofi’s Nobody Can Love You More that nearly sums up the writer’s interiorization of his subject, it has to be ‘I’m home.’ It is the end line of the second chapter titled ‘No Rooms of Their Own’. Soofi is in the red light district of Delhi on GB Road close to the seventeenth century Ajmeri Gate in Old Delhi. One evening, as Soofi surveys the GB Road corridor, now descending into the shadows of amorous dusk, besieged by pimps and customers, and women soliciting from their kothas, there is a sudden commotion with the arrival of the local police. Soofi is in front of Kotha No. 242, a stone’s throw from Kotha No. 300. With the police swooping in, all run for cover. Soofi too flees and bounds up the stairs leading to 300 or teen sau, the preferred nomenclature. ‘I rush to the second floor and enter teen sau. Nighat is sleeping on a mattress laid out on the floor. Sushma must be upstairs. I go to the other room. Sabir Bhai, Phalak, Omar, Osman and Masoom are watching Bigg Boss on TV. On seeing me, they look surprised for a moment and then delightedly exclaim, ‘Soofi! ‘I’m home.’ That cataclysm passes the moment he attains 300. Kotha No. 300 was literally home for Soofi as he lived, breathed and trawled the iconic GB Road for three years while writing this book. It was central to the story because ‘home’ meant empathy and an instinctive abhorrence of value judgement about those who ran and manned the world’s oldest profession. Soofi’s journey on GB Road begins with Sabir Bhai, who is the owner of teen sau, seeking a tutor who would take English lessons for his children. Soofi’s opening gambit is simple – a fine blend of Herman Melville and Jane Austen. ‘Take Sushma’, is all. The brisk beginning sets the stage for a remarkably unembellished and uncomplicated narrative strategy. Sushma, with whom Soofi forges a close relationship, sharing confidences, food and remembrances of things past, becomes the medium unfurling the archetypal story of a sex worker. Sushma, who was ‘Shireen’, is one of four or five women that Sabir Bhai keeps in his kotha. Hailing from Bangalore, though with an emotional perch in Meerut, where she first set foot in the trade, she had lost her mother early on. Her father remarried and her stepmother treated her badly. Soon a friend steps in and has her lured into the trade. The story repeats itself, be it Roopa or Mamta, with variations in the detailing of it. But regardless of context or geography, what emerges distinctly is that viscous river of compulsion or trickery into which our protagonists are often thrown. Sabir emerges as Soofi’s raconteur alter ego. He presides over the destinies of Sushma, Phalak, Nighat, etcetera. Phalak is his woman with whom he has four children, the youngest of whom is the ‘white-skinned’ and blonde Imran, in all likelihood, born out of her liaison with an American named John. Sabir and Phalak, both uncommonly dark, are exceptionally proud of the ‘white’ Imran. Soofi soon becomes family at teen sau. The women grow fond of him, fuss over him, and trust him. It is these relationships Soofi forges, a little gingerly in the beginning in and around teen sau, that bind the narrative. So is sex all on GB Road? No. Sex is purely commerce in the plying of which Sushma and her co-workers dream of a world beyond, embodied in that curiously used word ‘society’. In fact, society is a leit motif hard to ignore. It is the world on the other side of Shahjanabad – where ‘decent’ people live and pursue respectable professions and lives. In fact, some have graduated into society, such as Rajkumari’s daughters who have moved away but are dependent on her. In excavating, ever so gently, the inner worlds of his protagonists, lie Soofi’s skills as an amanuensis, connected, yet unconnected enough to lend the narrative clarity, compassion and authenticity. His narrative takes us on a contemplative trajectory. RV Smith’s memoirs are a valuable precursor. Smith, whom Soofi interviews for the book, is a storehouse of chivalric history. So what do we make of this world that ‘services’ the other side of the world? It is home to competing worlds – of gods, heavens, purgatories, holy books, passions, aspirations, loves, desires and hates. Look at Hasan Khurshid, an Urdu journalist, from the more kosher quarters just outside GB Road. Trained from childhood not to look up at the kothas where the women would display themselves, Khurshid pays tribute to them thus in Urdu poetry: ‘This is that woman/ Who in your eyes/ Is a woman only because of her body…’ Or look at Sabir Bhai’s young sons Osman and Omar, who want to get out of this life into one of respectability and who are convinced about the certitudes of afterlife, ‘… Allah will examine each of us, determining our good and bad deeds.’ Or look at Karun Abro, a sanitary-ware dealer in one of the shops below the kothas on GB Road, who takes exception to Soofi’s chance reference to GB Road as ‘uncivilized world’ and fires back: ‘GB Road is a part of our society. How can you say that they are not civilized? … but you will skip some aspects and highlight others. And this manipulation will shape the image you present to your readers.’ This cannot be but a sociological understanding of a high order. Sabir Bhai, who plans to write a book himself, has the last word: ‘I want to tell the world that the world outside GB Road is filthier. Imagine how much worse the situation would be if there were no red light areas…’ As the reviewer, I cannot but pay tribute to the power of the writerly voice. The voice, one of great clarity, dispassion, understatement, and utterly devoid of prescriptive judgement, is the unmistakable hero of the story. The narrative that flows seamlessly ably nuances the architecture of time, space and character. This book is as much a journey into the lives of those who inhabit GB Road as much as it is into the world without. It heightens as much as it mystifies the narrative experience.

|

Mayank Austen Soofi

Mayank Austen Soofi